Over the course of several years, through studying dozens of writings by migrants, I have come to realize that their minds often become fixed in the state they were in at the moment of migration.

Kabul 24: This mental fixation is such that each generation of migrants reconstructs the world using the narratives and vocabulary of that particular time.

For instance, those who left Afghanistan during the era of communist regimes remain, in their writings and words, entangled in the rivalries of “Khalq” and “Parcham.” They interpret the current world through those same dichotomies.

Another group, who migrated during the civil wars, repeatedly invoke terms like “ashrar,” “Shura-e Nazar,” “Hezb-e Wahdat,” “Seven-Party,” and “Eight-Party” in their discourse.

Similarly, those who left the country at the end of Ashraf Ghani’s government still reflect, in their writings and narratives, the political and administrative atmosphere of that era.

Yet, the current reality is neither a repetition of the Khalq and Parcham rivalries, nor a reenactment of the civil wars, nor a continuation of the republic era.

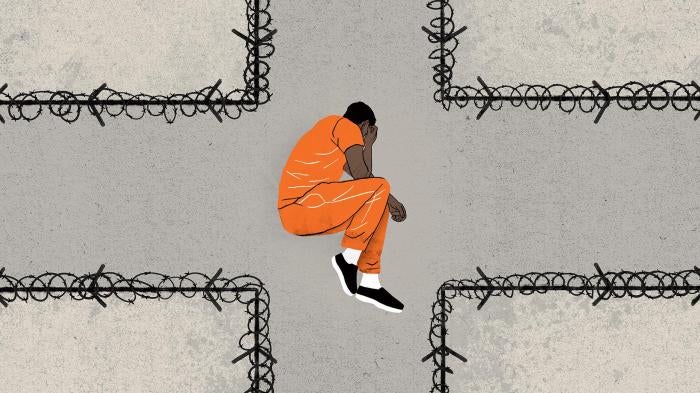

The present reality has a different form—one that must be felt existentially, lived through body and soul, and then described phenomenologically.Migrants are deprived of this experience because their connection to the “lived now” has been severed.

As a result, their minds have “frozen” at the moment of migration, remaining trapped within that historical frame.

The consequence of this frozen memory is clear: the narratives of migrants are predominantly past-oriented and, in many cases, do not align with today’s objective reality.

Consequently, an epistemological gap emerges between migrants and those living inside the country.

The insiders experience today’s reality with “flesh and blood,” while migrants reconstruct it solely through “historical memory,” and, as the poet says, send kisses to the moonlight from afar.